#2: Mark Richardson (Part 1)

My old flatmate opens the batting with John Aiken in my Development Squad - an absolutely terrible idea in real life. We discuss yips, onesies, metamorphoses and an unpaid phone bill ...

Note: this interview took place not long before Mark lost his role on The AM Show.

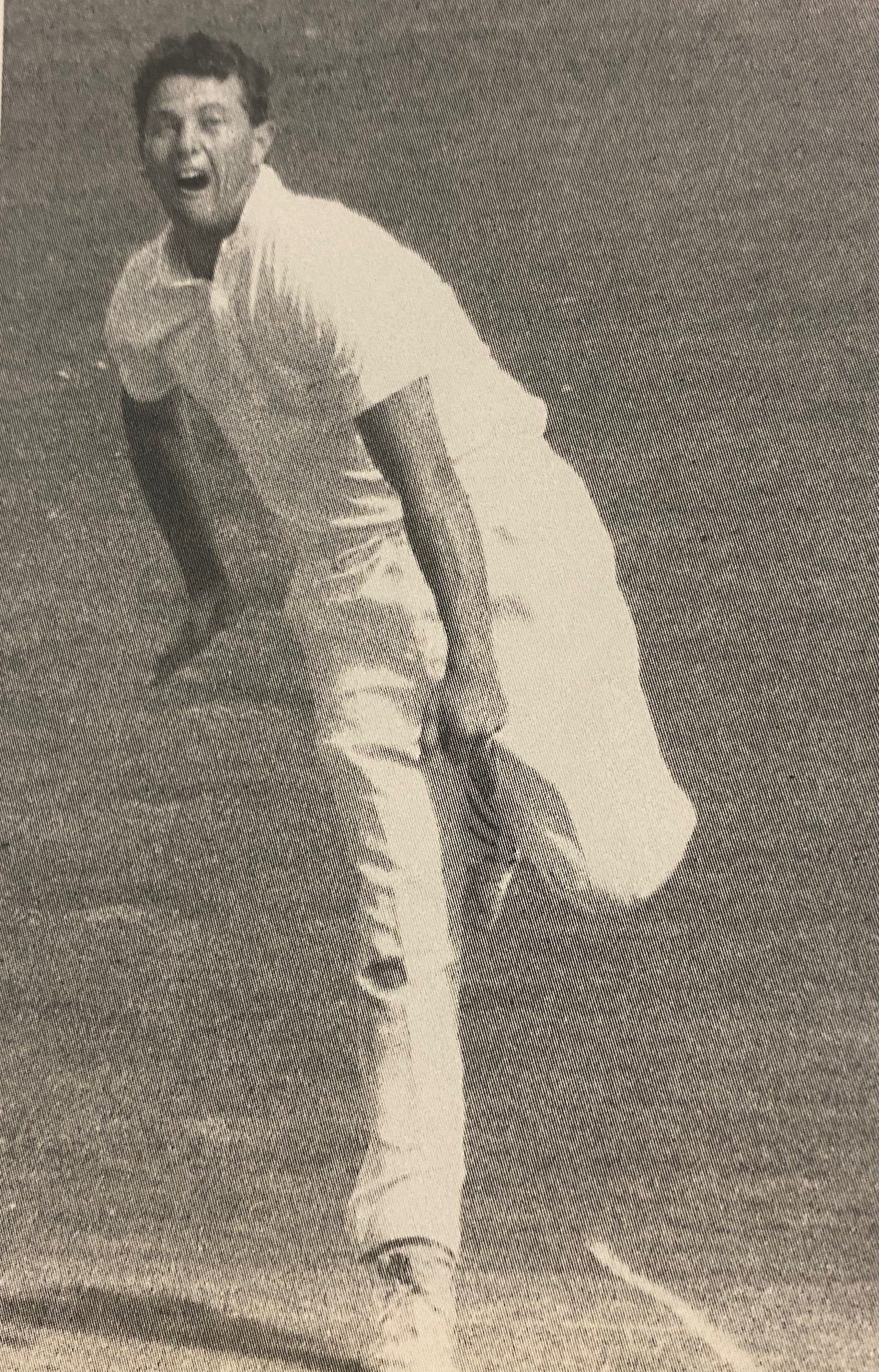

In 1992, Mark Richardson and I flatted together at 136 Taieri Road in Dunedin just down the hill from Wakari Psychiatric Hospital. As promising spin bowlers, we had both been lured south by Otago to fill the enormous boots of the retired Stephen Boock. As it turned out, neither of us were fit to tie his shoelaces. Shane Robinson, the Otago wicketkeeper and later a good friend, was our landlord. I was last to arrive and took a room in the burned out basement - Shane was a doer-upper and had gutted the downstairs that Mark and I shared. Two girls lived cosily upstairs. They had a soft spot for me - mothered me, to be fair - but Mark was the flat villain. He and ‘The Ice Maiden’ had a particularly frosty relationship.

Mark drove around in Wally Lees’s old yellow Sigma - surfboard in the back - and our ‘job’ was to visit schools and coach kids. Cricket didn’t work out as planned for either of us that year but we had fun. In those days, there was always laughter and a sense of drama around Mark - you could dare him to do something and he would do it. I recall a skyrocket war with our neighbours ending in a small, but angry fire. Two spin bowlers living together, fighting for the same spot and feeding off each other’s failures … The Ice Maiden must have been tempted to call Wakari and suggest that the outpatient experiment had gone on long enough.

In my ‘Letter to Ezra’, I wrote about Mark throwing in the bowling towel. He took a year-long surfing break from the game, but when he returned to club cricket, he seemed a different player. He opened the batting and smashed it, unveiling a rare back foot game, the mark of a quality batsman. That season, I captained Otago B against Canterbury B (shaking hands with my old friend, Gary Stead, at the toss). There had been nothing memorable about the game - we had been outplayed. The final over came, we were 33 runs shy, and Hamish Kember, a miserly left-arm spinner, took the ball. Mark proceeded to hit the first five balls of the over for six - as his team mates went incrementally berserk on the boundary. He reckoned the last ball was in the slot, too, but he edged it and it trickled away for three - perhaps even more remarkable, given the size of Geraldine Oval and Richie’s notorious lack of speed.

Mark’s dam of self-belief broke. Before the end of the season, he was recalled to the Otago team as a dashing middle-order batsman. When Otago played the West Indies at Carisbrook, Richie thought it a good idea to chirp Brian Lara, to shame the great man about his dismissal to Zoe Goss in a charity match. In retaliation, Lara ordered his fast bowlers to bombard Mark. He scored a run-a-ball century, hooking and cutting Benjamin, Cummins & co. into the empty terraces. Most people are unaware of that raw ability, but thanks to two character traits - the ability to recognise an opportunity and to adapt - Mark saw the only chance for him to make the Blackcaps was to cut risk from his game and become the dour opening batsman that the New Zealand public remembers.

Mark admits that his role on The AM Show is to act the clown but he is nobody’s fool. Certainly, he has never lost the talent for making a spectacle of himself - Mark’s cramping incident in India has over 4 million YouTube views and brought Prime Minister Ardern to tears - but he has also leveraged this comic talent. One of the keys to his success - besides great tenacity - is an air of failure, but his various transformations have shown that he should never be underestimated. Of course, that is precisely what people have done. Mark can be easy to dismiss, to laugh off, but behind the one-liners there is an element of calculation, a method to his madness. He presents as an enigma because he wants people to think, ‘‘Is he for real? Does he mean that?’ I want to leave them guessing.” He has consistently played off versions of himself to reinvent his career over and over, literally shedding skins in the case of the beige Cathy Freeman onesie.

We hadn’t spoken properly in over twenty years, but we laughed for two hours. We started with our kids - Mark has 14 year-old twins. He expressed some shock that both his kids are good athletes - his son came fourth in the 800m for Auckland schools and even has enough speed to play on the wing.

‘I don’t think he’s my son.’

‘You haven't passed on the beige Cathy Freeman - as an heirloom?’

‘No, but he would look better in that than I did. That outfit became a rod for my back. It was like a ghost - I couldn’t get rid of it. Someone actually bought it for $1000. I donated that money to the IHC [a charity that provides services for people with intellectual disabilities], and then ten or eleven years later, this guy rang up out of the blue and said, “Hey, I've got your old beige running suit. Do you want it back?” So I met him in the car park at Sky and he returned it. From there, I gave it to the museum at the Basin Reserve, and last I saw it was on Jeremy Coney’s mannequin, which made me laugh because if Jerry ever saw that he'd die. He’d be outraged.’

We started our interview proper with some mutual appreciation. I told Rich how much I had enjoyed his book, Thinking Negatively. The bargain bins groan with tawdry, ghostwritten autobiographies, packed with photos and containing little more than a matey sequence of numbers, a coupla beers and a dash of subcontinental diarrhoea. Thinking Negatively was different: it was unsurprisingly funny but also bold and honest - a self-dissection in which he exposed his inner workings. The book could serve equally as a guide or warning to the pitfalls of professional sport.

‘I wanted people to read a book that was different but also practical, one that didn’t require you to be a cricketer. I'd read so many bloody self-help books, so I thought I’d write one my way. It still needed elements of autobiography, so it was something of a hybrid. It was quite therapeutic, setting it down and facing it. I remember trying to read Justin Langer’s book and it was like reading a strawberry milkshake. I thought, ‘Surely you don't believe what you’ve put down on paper here.’ I wanted to write something that was honest.’

‘The article you wrote resonated with me … very much so. It was me. I basically felt I was reading about me. I had those moments that got me across the line when I started taking batting seriously and I look back and think, ‘God that was lucky!’ But then you have to be good enough to make the most of that luck, to back it up. I went through what you were going through, without a doubt. It just didn't work out on the field for you. It very easily could have been me as well. I was fortunate to have a Plan B, I guess.’

‘I still remember going to those spin bowling clinics and - when I was allowed to pad up - always batting really well. After one session, it struck me. I thought, ‘Just balls up! Show some balls and play like this against quicker bowling.’ The other aspect to my transformation, if you want to call it that, happened when I came back from taking that holiday, that year out. I started playing for North-East Valley [Dunedin club side] and started realising it was a game again and that it could be fun. I still wanted to do really well - but I really enjoyed playing, and because it was club cricket, I batted higher in the order. My bowling was still fine at that level - you can bowl one long hop per over and get away with it. And I had success - scored runs and took wickets - and the more runs you make, the more you want, so I learned how to stay in. I put a lot of that transition down to the simple fact that I started to enjoy playing cricket.’

‘Ironically, at the end of my career, I hated club cricket with a passion because I got to the point where my game wasn’t suited to it any longer. I couldn't smash balls through the covers against medium pacers or slog over cow corner. The ball I used to work off my hip would hit the long grass at square-leg and I’d get one run if I was lucky. I was at a point where I was reading my press too much, so I wasn't prepared to back myself to go outside my game plan and just whack it. I also hated it because people would think I was arrogant, that it was below me and that I wasn't trying. But I was just no good at it.’

‘I had also developed a real desire not to give my wicket away. I can remember managers at Otago coming into the dressing room and accusing us of being gutless, without understanding the quality of the cricket we were involved in, but it used to pull on my heartstrings and I hated it. I hated giving my wicket away. When I started playing, everyone used to say, ‘Richie's afraid of the short ball’, so some ego took over to a certain extent, too. It became about gritting my teeth and proving to everyone that I had some courage. In Test cricket, I don't think I ever stopped being a little frightened of the ball, but I hated getting out because I’d given into that fear.’

I asked Peter Roebuck’s question: ‘Does cricket draw people of a fragile nature?’

‘No, I don't think it does. I think it draws people of all types. I think there have always been pin-up boys who some might say were fragile, but I don't think it's because they are cricketers. They’d probably be like that in any work environment that tests them. It's a game where you have to learn to deal with failure. In cricket you can be the best player in the world and you are going to get a duck in a pressure situation and lose the game. How are you going to deal with that? Because it will happen at some point in your career. I certainly think cricket would make some people fragile.’

‘Sport and mental health are in the news at the moment and I was trying to make a point the other day that you can’t blame sport because it will always beat people up. Sport will always confront you with pressure and you will fail, and you will let yourself down. I just think now we're trying to say that sport is the cause of mental health issues. I don't think it is. I think that people with mental health issues are also playing sport because the full gamut of people get involved. Some commentators say sport is a tough environment. Well, most workplaces are tough environments and they all have their pressures. I was really frustrated. It felt like all of a sudden I was being vilified. Sport is where people who want to face heat and pressure can test themselves.’

I liked a quote from his book from Stephen Fleming, ‘Don't you dare give in to yourself.’

I forget when that was, but he was sensing I was starting to crumble and I was about to have a fly, or charge down the wicket. I think he was at a point in his captaincy where he was trying to get inside his players' heads and understand them. He was trying to get me to step outside mine for a moment! I enjoyed batting with Flem, but even after putting on a good partnership with him, if you got out, he would give you a filthy look as you walked off - ‘Mate, what are you doing?’ I made a lot of 70s and 80s [Mark scored four Test centuries but was dismissed twelve times between 70 and 100] and often Flem was at the other end. He wasn’t angry - he was disappointed in you. Like a parent. But he was right. Most of the time you do give into yourself, the little man on your shoulder telling you it's too difficult. It was always a battle - the little man was always there.’

‘Nashy once said something that stuck with me. It was probably when you and I were flatting together in Dunedin. He was playing for Taieri. I’d had a bad game and I was out practising after the match, beating myself up basically, bowling by myself in the nets. He came out of the bar. I thought, ‘Here comes Nashy. He’s probably going to come and say something nice. Come and have a beer or something.’

He said, ‘You fuck me off!’

‘Eh? What?’

‘You fuck me off because you think no-one else goes through what you do,’ and then he walked away.

He was so right - basically, ‘Stop feeling sorry for yourself and learn to get over it.’

‘One of the skills I eventually picked up - probably when I went from being a good Otago player to getting the runs I needed to break into the Blackcaps - was learning how to perform ‘uncomfortable.’ I've seen many guys - classic net players - who had to be comfortable. They want to feel great all the time and take sides apart, and when it isn't comfortable, they don’t survive. They can’t play ugly. It's a skill you have to learn if you want to bat for long periods of time. ‘I remember Graham Gooch saying, ‘Always train harder than you play.’ Every now and again, you would come across some horrible nets. I'd force myself to go in and see if I could survive for half an hour. Other players would say, ‘I’m not going to bat on that.’ They wanted to smash the bowlers with old balls and feel great about themselves - each to their own - but I knew that I had to struggle at training to get a little confidence in the middle. If you seek comfort in cricket, I don't think you'll be successful.’

‘It doesn't surprise me that I burnt out quickly, but it's the reason I got there. I'm pretty proud of what I achieved. I still think that my record is better than what it should have been. Most players will say the opposite, of course. It's not world class by any stretch of the imagination, and I might have said this in the book, but while I was there for a fleeting moment only, I was actually there properly and achieved some things.’

The second instalment will be delivered to your inbox on Friday morning!